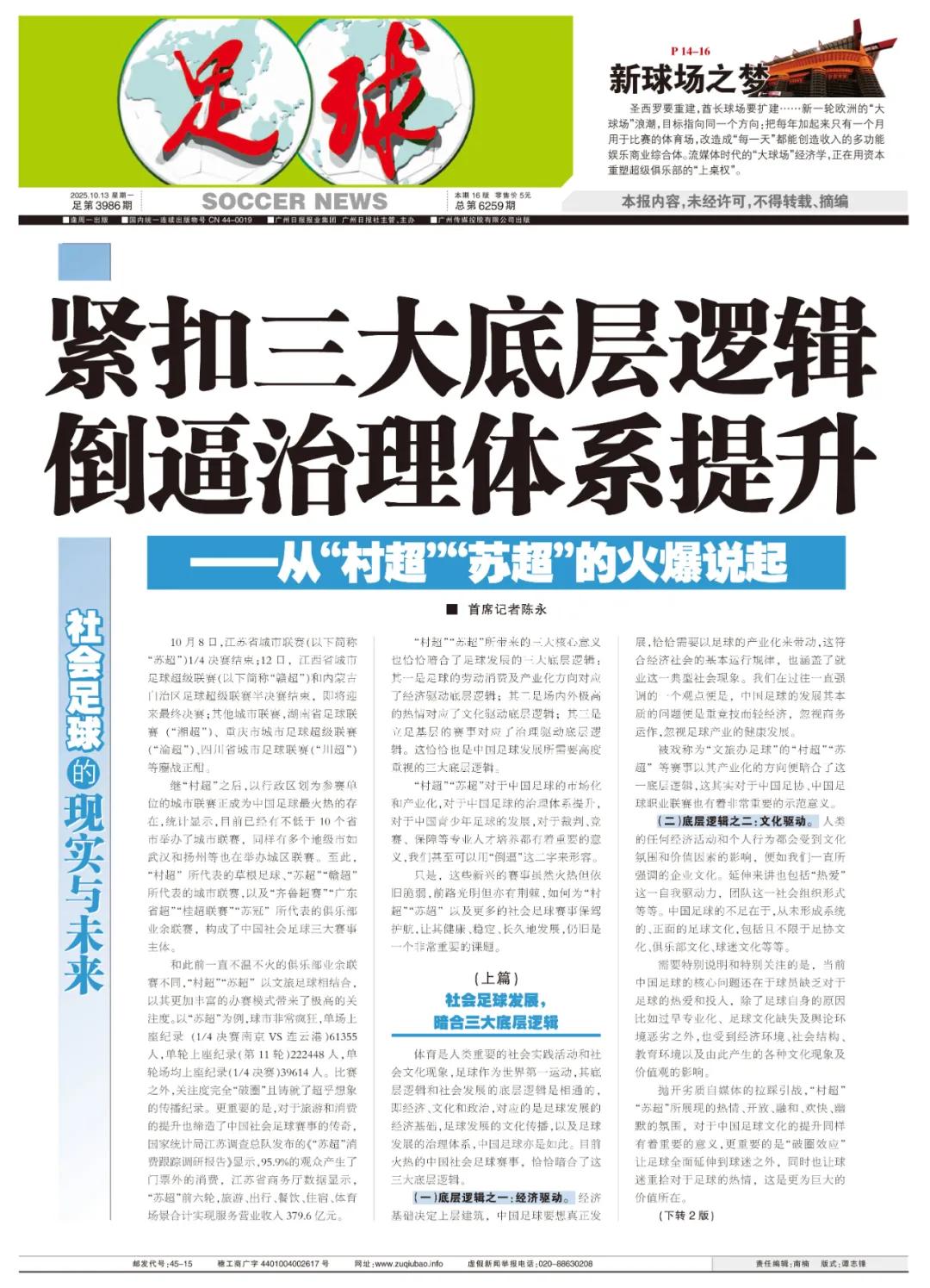

Revisiting the "Su Super League": The Reality and Future of Social Football

Chief Reporter Chen Yong reports On October 8th, the quarterfinals of the Jiangsu Provincial City League ("Su Super League") ended; on the 12th, the semifinals of the Jiangxi Provincial City Football Super League ("Gan Super League") and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Football Super League finished, with the finals imminent; meanwhile, other city leagues like the Hunan Provincial Football League ("Xiang Super League"), Chongqing City Football Super League ("Yu Super League"), and Sichuan Provincial City Football League ("Chuan Super League") are in intense competition.

Following the "Village Super League," city leagues organized by administrative divisions are becoming the hottest phenomenon in Chinese football. Statistics show that at least 10 provinces and cities now hold city leagues, and several prefecture-level cities such as Wuhan and Yangzhou also run urban area leagues. Together, grassroots football represented by the "Village Super League," city leagues like the "Su Super League" and "Gan Super League," and amateur club leagues such as the "Qilu Super League," "Guangdong Super League," "Gui Super League," and "Su Crown" form the three main pillars of social football competitions in China.

Unlike the previously lukewarm amateur club leagues, the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" combine cultural tourism with football, offering richer event formats that attract significant attention. For example, the "Su Super League" has a fanatical fan base, setting a single-match attendance record of 61,355 (quarterfinal Nanjing vs. Lianyungang), a single-round attendance record of 222,448 (Round 11), and an average per-match attendance record of 39,614 (quarterfinals). Beyond the games, the attention has broken through traditional boundaries, creating unprecedented media coverage. More importantly, it has boosted tourism and consumption, creating a legendary impact on Chinese social football events. According to the Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics’ "Su Super League Consumption Tracking Report," 95.9% of spectators made purchases beyond tickets, and data from Jiangsu’s Department of Commerce shows that in the first six rounds of the "Su Super League," combined revenue from tourism, travel, dining, accommodation, and sports-related services reached 37.96 billion yuan.

The three core significances brought by the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" precisely align with the three fundamental logics of football development: firstly, the labor consumption and industrialization direction of football correspond to the economic driving logic; secondly, the intense enthusiasm inside and outside the field matches the cultural driving logic; thirdly, grassroots-based competitions correspond to the governance driving logic. These are exactly the three fundamental logics that Chinese football development must highly prioritize.

The "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" play a crucial role in the commercialization and industrialization of Chinese football, the improvement of football governance systems, the development of youth football, and the cultivation of professional talents such as referees, competition officials, and support staff. We can even describe this impact as a form of "forcing progress."

However, although these emerging competitions are popular, they remain fragile; their future is bright but also fraught with challenges. How to safeguard the "Village Super League," "Su Super League," and other social football events to ensure their healthy, stable, and sustainable development remains a critical issue.

Sports are a vital form of human social practice and cultural phenomenon. Football, as the world's most popular sport, shares fundamental logics with social development, namely economy, culture, and politics, which correspond respectively to the economic foundation of football development, cultural dissemination, and governance systems. Chinese football is no exception. The currently thriving Chinese social football events perfectly reflect these three fundamental logics.

(1) The first fundamental logic: Economic drive.

The economic base determines the superstructure. For Chinese football to truly develop, it must be driven by the industrialization of football, which aligns with basic economic and social operation principles and includes employment as a typical social phenomenon. A long-held viewpoint is that the core issue in Chinese football development is the overemphasis on competition and neglect of economic aspects, ignoring business operations and the healthy growth of the football industry.

The so-called "cultural tourism football" events like the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" embody this industrialization direction, which also serves as an important example for the Chinese Football Association and professional football leagues in China.

(2) The second fundamental logic: Cultural drive.

All human economic activities and personal behaviors are influenced by cultural atmosphere and values, much like the corporate culture we often emphasize. Extending this includes self-driven passion ("love") and social organizational forms like teams. A major shortfall in Chinese football is the absence of a systematic, positive football culture, including but not limited to the cultures of the football association, clubs, and fans.

It is particularly important to note that a core problem in Chinese football today is players' lack of passion and commitment to football. Besides football-related reasons such as premature specialization, cultural deficiencies, and a poor public opinion environment, this is also influenced by economic conditions, social structures, educational environments, and the resulting cultural phenomena and values.

Putting aside the negative trolling from low-quality social media, the enthusiasm, openness, inclusiveness, joyfulness, and humor shown by the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" are significant for improving Chinese football culture. Even more importantly, the "breaking the circle" effect extends football beyond just fans and helps fans regain their passion, which is a far greater value.

(3) The third fundamental logic: Governance drive.

If culture is the "soft support" for social and economic development, governance systems are the "hard support." Although football has become a top global sport, its initial development was grassroots-based, starting from communities, factories, and other groups, gradually expanding to national teams and professional leagues. The often-discussed competition system pyramid and youth development pyramid are also built on this foundation. China's football governance system is mainly top-down, which is crucial for development, but only with active bottom-up engagement and promotion can Chinese football truly revive. The national football work meeting on July 31 focused on encouraging local football development, serving as a rallying call for unity and effort.

Grassroots football represented by the "Village Super League," city leagues like the "Su Super League," and amateur club leagues have maximized grassroots enthusiasm, creating a bottom-up complement to the top-down governance system, achieving mutual reinforcement. This has two extended significances: first, it breaks the old mindset—Chinese football can be played this way! Chinese football can be this popular! Second, this governance model pressures the football governance system itself, with multi-level government departments at town, county, city, and provincial levels actively contributing, providing positive examples and impetus for the Chinese Football Association, China Football Federation, and other related governance bodies.

Beyond aligning with the three fundamental logics, the flourishing of social football also holds great value in specific areas such as referee development. During interviews, many places lamented that while other aspects are fine, referees face immense pressure. In fact, the growing number of social football events inevitably promotes the growth and improvement of referees, coaches, support staff, and competition officials. For example, Chinese referees rarely officiate matches with spectators except for international-level and national-level Chinese Super League referees. Where would their growth come from? It's no surprise if they struggle in the Super League; performing well too early would defy natural growth patterns. Yet now, social football matches with over 10,000 or even 20,000 to 30,000 spectators are common, allowing referees to develop in such environments, making future challenges in the Super League and lower leagues less daunting.

Social football events may not yet show direct value for youth football development, but this is not the case. They hold multiple layers of value: first, they influence parents—simply put, parents who don't watch football rarely encourage their children to play. Currently, most Chinese youths' development paths are parent-directed. The "Su Super League Consumption Tracking Report" shows that 95.2% of Jiangsu residents are aware of the "Su Super League," far exceeding the fan base and demonstrating huge national influence. Other city leagues are also very popular. Second, they directly affect youth players, which needs no further explanation. Third, they comprehensively promote the growth of social youth training institutions, which, combined effectively with school football, are key to raising youth football standards.

However, for the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League" to maintain long-term, stable, and healthy development, greater efforts from all parties remain necessary. Before discussing this, it is essential to reposition the city leagues represented by the "Su Super League."

The grassroots football represented by the "Village Super League" is actually a crucial organizational form in world football, occupying the foundational level in football development globally: community football. Amateur club leagues need no further explanation. In European football, the pyramid system with around 10 tiers is mainly composed of clubs. However, aside from national team competitions, administrative division-based leagues are not mainstream in global football development.

In China, with its vast territory, large population, and advanced economic development, combined with over 2,000 years of the historical county system and the strong local attachment among Chinese people, city leagues based on administrative divisions have deep roots. Globally, football development models vary: European youth football is club-focused; the U.S. emphasizes school football; Japan balances both; Europe has a complete pyramid system; Brazil, besides national professional leagues like Serie A and B, also values state-level professional leagues such as the São Paulo State Championship. For Chinese football, city leagues and amateur club leagues can coexist without conflict, though coordination of schedules and naming is essential.

Returning to the future development of social football events like the "Village Super League," "Su Super League," and amateur club leagues, challenges such as scheduling conflicts between city leagues and amateur club leagues and relatively heavy administrative costs will be analyzed in subsequent chapters of this series. Here, the focus is on how social football events can be integrated into the national football development system for orderly growth, thereby supporting the revitalization of Chinese football. It is important to clarify that this integration into the national system does not mean the media-hyped takeover by the Chinese Football Association but involves comprehensive planning, layout, and coordination at the national level.

(1) Sustained and high-level attention from national and provincial/city governments. The popularity of the "Su Super League" has fully driven the development of city leagues, spawning more city leagues or prompting reform of traditional competitions. It has also led to a surge in traditional amateur club leagues such as the "Qilu Super League" and "Guangdong Super League." Statistics show that following the "Su Super League," over 10 provincial-level city leagues have been established, including "Gan Super League," "Xiang Super League," "Chuan Super League," "Yu Super League," "Meng Super League," "Liao Super League," "Qing Super League," "Qiong Super League," and "Dian Super League." It is expected that by 2026, the number of provinces and cities hosting city leagues will likely exceed 20.

However, stability is more important for football development. Just like the Chinese professional football league, which has experienced packed stadiums, empty stands, and financial ups and downs over 33 years, the path has been bumpy. Fortunately, the national government currently places great emphasis on social football, especially city leagues, with provincial and city governments equally proactive. Departments of publicity, sports, and culture tourism are highly engaged. Moreover, the current social and economic environment fosters the growth of sports and entertainment industries, laying a foundation for the sustained and stable development of city leagues. This steady attention must continuously mobilize resources to safeguard social football events as vital components of social and economic development.

(2) Equal emphasis on city leagues, amateur club leagues, and professional football. A concerning trend is that due to the popularity of city leagues, some localities may overly pursue city league events while neglecting the development and construction of professional clubs and amateur club leagues. Considering the uneven economic and football development across provinces and cities, at least coastal provinces, municipalities, and economically stronger inland provinces such as Sichuan, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Anhui, Shaanxi, and Jiangxi should maintain balanced development across these three levels.

(3) Promoting nationwide and cross-regional social football competitions. Currently, social football events are mostly single province- or city-level competitions. In the future, it is necessary to promote national and cross-regional social football events, such as launching national-level provincial-city leagues based on provincial city leagues, with player selection, tournament formats, and possibly, after coordinated scheduling, home-and-away matches in pilot regions like Jiangsu-Zhejiang-Shanghai, Hubei-Anhui, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei-Shandong-Henan. Extending this, regional professional leagues paralleling professional leagues could be tried in areas like the Greater Bay Area, Jiangsu-Zhejiang-Shanghai, and Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei-Shandong-Henan, utilizing international match days, winter breaks, and summer breaks. This topic was mentioned several years ago.

(4) Necessary organization and coordination to safeguard social football events. An interesting case: when the Shandong Qilu Football Super League started, ordinary fans besides seasoned ones mistakenly thought "Qilu Super League" and "Su Super League" were the same, and some media workers shared this misunderstanding. Most people abbreviated both as "Lu Super League," very similar to "Su Super League." As a result, Shandong Province unified the abbreviation as "Qilu Super League." In Jiangsu, the provincial amateur club league originally named "Jiangsu Province Amateur Football Club Super League" is now called "Jiangsu Province Football Club Championship League," abbreviated as "Su Crown." Currently, at least at provincial and city levels, city leagues based on administrative divisions can be uniformly abbreviated as two-character "X Super," while amateur club leagues can be abbreviated as two-character "X Crown" or other multi-character abbreviations. Of course, corresponding schedule coordination is also essential.

(5) Necessary guidance of public opinion. During the development of the "Village Super League" and "Su Super League," there have been incidents of low-quality social media spreading rumors, negative comparisons, and provocations. For example, the rumor that the "Su Super League" was forced to rename led to strict governance of social media platforms. For the development of Chinese football—whether for the national team, professional leagues, or city leagues—a healthy public opinion environment is indispensable. Although rumors and provocations may temporarily generate traffic, their long-term negative impacts and potential backlash are more damaging. Countermeasures include strict regulation, proactive clarification, and guidance by media and quality social media. In fact, even for media focused on traffic, the healthy development of all levels and types of leagues better serves their interests.

Wonderfulshortvideo

User PlaymakerHub has posted a video.

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App