Three major Southeast Asian football powers have collectively dismissed their head coaches over the past year.

The leading Southeast Asian teams, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, have simultaneously ended their relationships with their head coaches in a span of just over one year.

Within a little more than a year, the three strongest Southeast Asian teams—Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia—have all said goodbye to their head coaches, highlighting the intense pressure and harsh realities of the regional football environment where performance demands weigh heavily on managers.

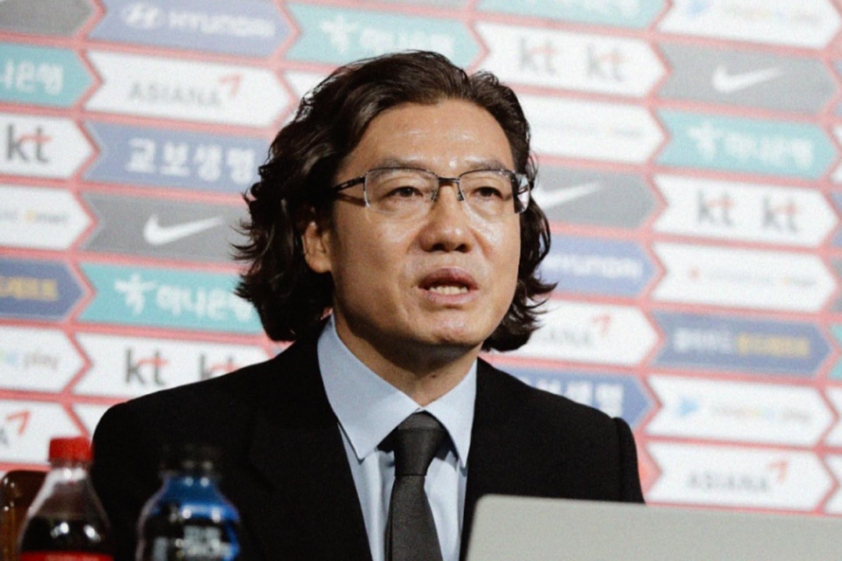

In Malaysia, coach Kim Pan-gon resigned after failing to guide the team past the second round of the 2026 World Cup qualifiers. Earlier, the South Korean coach had sparked excitement by leading Malaysia to two consecutive wins against Kyrgyzstan and Chinese Taipei, temporarily topping their group.

This achievement led the Football Association of Malaysia (FAM) to extend his contract until the end of 2025. However, the momentum did not last. Malaysia declined during the crucial stages, suffered consecutive defeats, and was eliminated early. The mutual termination of the contract a year early was seen as a “gentle end” to an unfinished journey.

Not only Malaysia, but Indonesia also recently underwent a similar coaching departure. After replacing Shin Tae-yong, Patrick Kluivert brought new hope to Indonesian football. Despite a 1-5 loss to Australia in his debut, two victories over Bahrain and China helped Indonesia make history by reaching the fourth round of the 2026 World Cup qualifiers.

However, in this round, Kluivert’s team quickly “came back down to earth” with consecutive losses to Saudi Arabia and Iraq, leading to an early exit. This result forced the Indonesian Football Association (PSSI) to decide to part ways with the Dutch coach, despite his contract lasting less than a year.

In Thailand, coach Masatada Ishii was not spared from the coaching changes. Although he helped the “War Elephants” maintain stability with a 53% win rate over 30 matches, this was still considered insufficient given FAT’s expectations for the team to excel in major tournaments. Differences in direction and coaching philosophy between the parties became the final straw, resulting in an early separation.

These three almost simultaneous coaching overhauls demonstrate that Southeast Asian football is entering a more fiercely competitive phase. Federations are no longer patient with long-term projects, while pressure from fans and media keeps the head coach position extremely volatile.

Short-term success now seems to be the only measure for a coach’s survival, and in a region where a single loss can trigger waves of criticism, coaches—whether Korean, Dutch, or Japanese—must accept one reality: there is no room for patience in Southeast Asia.

Wonderfulshortvideo

amorim press conference amorim interview cunha goal today mbeumo goal today manchester united 4-2 brighton manchester united 5 wins in a row manchester united hair guy

yamal ig story yamal instagram story el clasico yamal yamal barcelona vs real madrid

“We’ve got a lot of players that can put it in the back of the net” ⚽️

“On a personal note, it was a nice moment” 🙌

liverpool 2-3 brentford salah goal slot press conference slot interview

“We were a bit unlucky”

van dijk vs brentford brentford 3-2 liverpool

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App