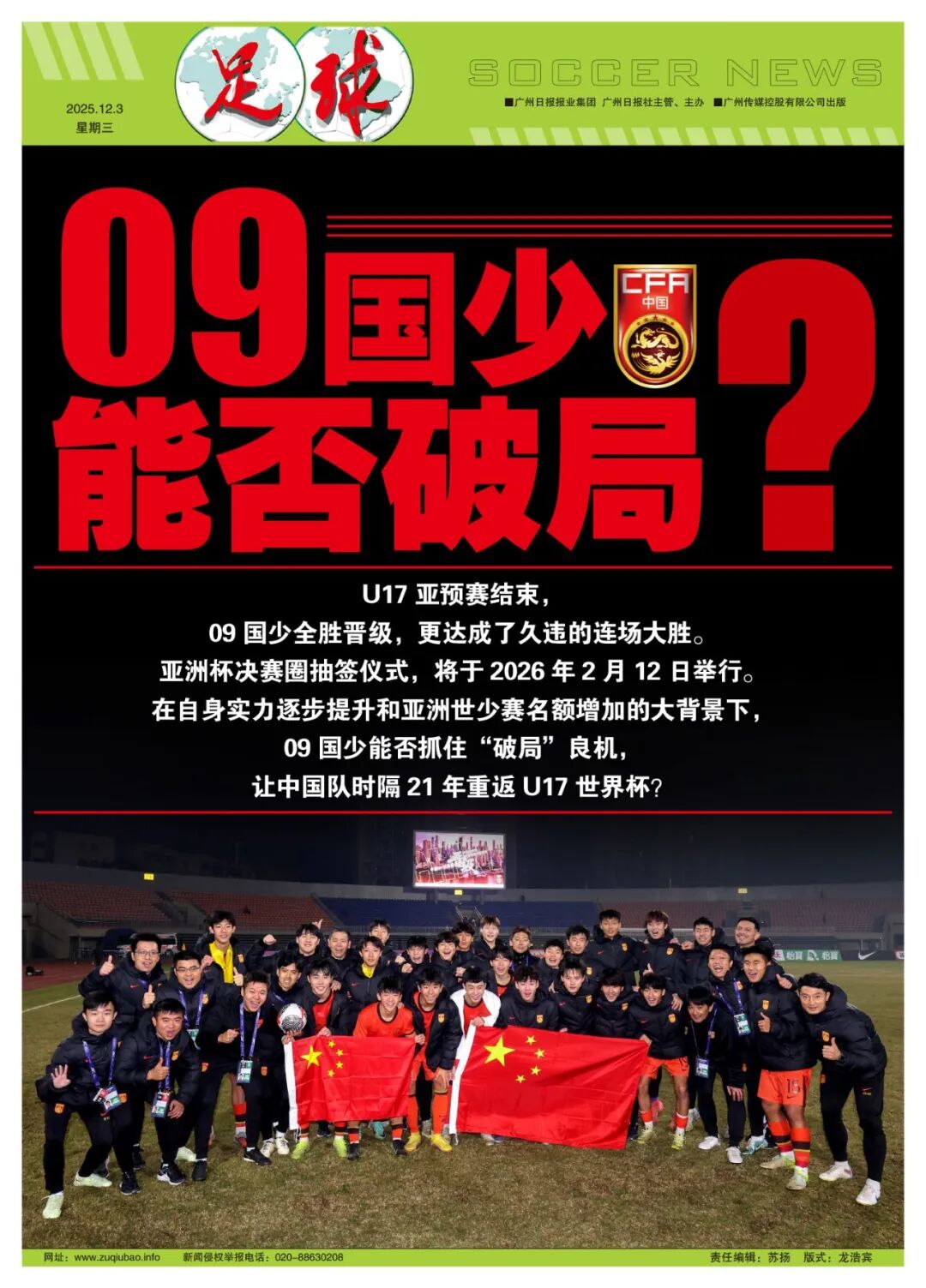

Making an impact at the U-17 World Cup! Draw for the Asian U-17 Championship places China’s 2009 youth team in the third pot—can they seize this breakthrough opportunity?

Written by Han Bing The U17 Asian qualifiers have ended with the 2009 Chinese youth team undefeated and advancing. The draw for the final tournament of the Asian Cup is scheduled for February 12, 2026. Seeding is determined by cumulative weighted scores from the last three U17 Asian Cups—China will be grouped in the third pot with Thailand, Vietnam, and India.

Earlier this year at the U17 Asian Cup, the 2008 youth team was highly anticipated but unfortunately lost to the eventual finalists (Uzbekistan and Saudi Arabia) and exited the group stage early. However, looking on the bright side, over the past three U17 Asian Cups, the Chinese U17 team’s performance has been steadily improving, climbing from 19th to 13th and then 11th place.

Given the gradual improvement in their own strength and the increase in Asian U17 World Cup slots, can the 2009 youth team seize this “breakthrough” chance and bring China back to the U17 World Cup for the first time in 21 years?

The participants for the 2026 U17 Asian Cup have all been confirmed, and the seedings basically reflect the current strength hierarchy of U17 national teams in Asia. South Korea reached the semifinals 4 times in the last 5 editions and the final twice; Japan made the semifinals 7 times in the last 9 editions and won 3 titles; Uzbekistan reached the quarterfinals 7 times in the last 8 editions, with 3 finals appearances and 2 championships. Among the top-seeded four teams, Japan, South Korea, and Uzbekistan need no introduction. Saudi Arabia is the weakest but benefits from hosting and still finished as runner-up last year.

Australia, in the second pot, is a traditional powerhouse, reaching the quarterfinals 6 times in the last 8 editions, though their recent form has dipped. Last time they were in a tough group with Japan, UAE, and Vietnam and failed to advance. Tajikistan and Indonesia have emerged as dark horses recently, but their results are inconsistent: Tajikistan reached the final in 2018 but exited in the group stage in 2023; last edition they topped a group with North Korea, Oman, and Iran but lost to South Korea on penalties in the quarterfinals. The Indonesian U17 team, like their senior side, relies increasingly on naturalized players but progress remains limited. Yemen may be the most mysterious team in the second pot, alongside third-pot regulars Vietnam, Thailand, and India, all of whom typically exit at the group stage.

Notably, India caused the biggest upset in the qualifiers by defeating Iran at home in the final round, knocking the latter out. Iran is a traditional powerhouse that has reached the quarterfinals 7 times, semifinals 5 times, and finals 3 times in the last 10 editions, ranking at least in the second pot. India narrowly missed the 2025 U17 Asian Cup last year due to goal difference but showed promise by drawing 1-1 with Vietnam and narrowly losing 0-1 to Uzbekistan in 2023, proving their strength is no longer negligible.

The fourth pot includes UAE, Qatar, Myanmar, and North Korea. Among these, North Korea is the biggest variable. In the last 9 editions, they reached the semifinals 6 times, winning the championship twice and finishing runner-up twice. Their strength is only slightly behind Japan and even surpasses South Korea. In the last U17 Asian Cup, they crushed Indonesia 6-0 to reach the semifinals and advanced from the group stage alongside Japan, South Korea, and Uzbekistan in the U17 World Cup. However, North Korea did not register for the 2023 U17 Asian Cup, causing their ranking to drop, placing them in the fourth pot for both 2025 and 2026 editions.

The first pot teams—Japan, South Korea, Uzbekistan—have shown consistent performance recently. Saudi Arabia, as the five-year consecutive U17 Asian Cup host, enjoys home advantage. Combined with the strong North Korean team in the fourth pot, these five teams form Asia’s current top tier in U17 football. Clearly, for China’s U17 team to break into Asia’s top 8 next year, they must face the challenge of these first pot powerhouses and also assert themselves against the second pot teams.

One encouraging sign is that China’s U17 team has steadily improved its rankings over the last three U17 Asian Cups. This year, the 2009 age group set a historic record in the qualifiers with a perfect 5 wins, scoring 42 goals without conceding any. This performance fuels fans’ high hopes for a “qualitative leap” at next year’s U17 Asian Cup. Although the team still lacks full stability, their warm-up matches show they can compete evenly against teams like South Korea and Australia. Simply put, apart from the five first pot teams, China can challenge any other opponent, and unless placed in an extremely tough group, the 2009 youth team has every reason to aim for a quarterfinal berth.

Additionally, since Qatar is the host of the U17 World Cup for five consecutive years, they automatically qualify. If Qatar reaches the quarterfinals, other Asian teams finishing third in their groups can still have a chance to enter a playoff for the ninth and final U17 World Cup spot, improving qualification odds compared to before. With the U17 Asian Cup now held annually due to the World Cup expansion, the global U17 football scene is entering a new cycle—offering a genuine opportunity for Chinese football, which has long struggled to progress from youth to senior levels.

As youth training numbers and quality begin to rebound significantly, although China’s youth teams still lag behind the top tier, they now have a real chance to break into Asia’s top 8 at the U17 level. If we can capitalize on this new cycle and maximize the benefits of improving youth development, China could qualify for the U17 World Cup repeatedly. This would not only build valuable experience for the youth teams but also provide a realistic pathway for Chinese football to rejoin Asia’s second tier, creating a positive cycle across all national youth levels.

Wonderfulshortvideo

messi aura lob, messi vs netherlands messi world cup 2022 argentina vs netherlands world cup 2022 que mira bobo messi bobo

declan rice man of the match arsenal 3-1 bayern munich declan rice vs bayern

haaland goal haaland goals today haaland goals yesterday haaland world cup qualification haaland norway world cup qualification

barcelona broke lewandowski goal camp nou reopening barcelona

mbappe goal today mbappe goals mbappe highlights

estevao goal today chelsea 3-0 barcelona estevao vs barcelona estevao instagram story estevao highlights today

florentino perez real madrid florentino perez leaving real madrid

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App