The inevitable trend: football “managers” are becoming increasingly rare

Written by Han Bing The back-to-back sackings of Maresca and Amorim have ignited intense discussions across European football concerning the distinction between “managers” and “head coaches.” The top four leagues in Europe have long adopted a dual leadership model where head coaches collaborate with sporting directors. While the Premier League traditionally maintained the “manager” role encompassing all first-team affairs, the surge of capital investment, increasing commercialization, and corporate structuring of elite clubs have led to larger, more complex organizations. Consequently, dividing first-team authority has become the mainstream approach.

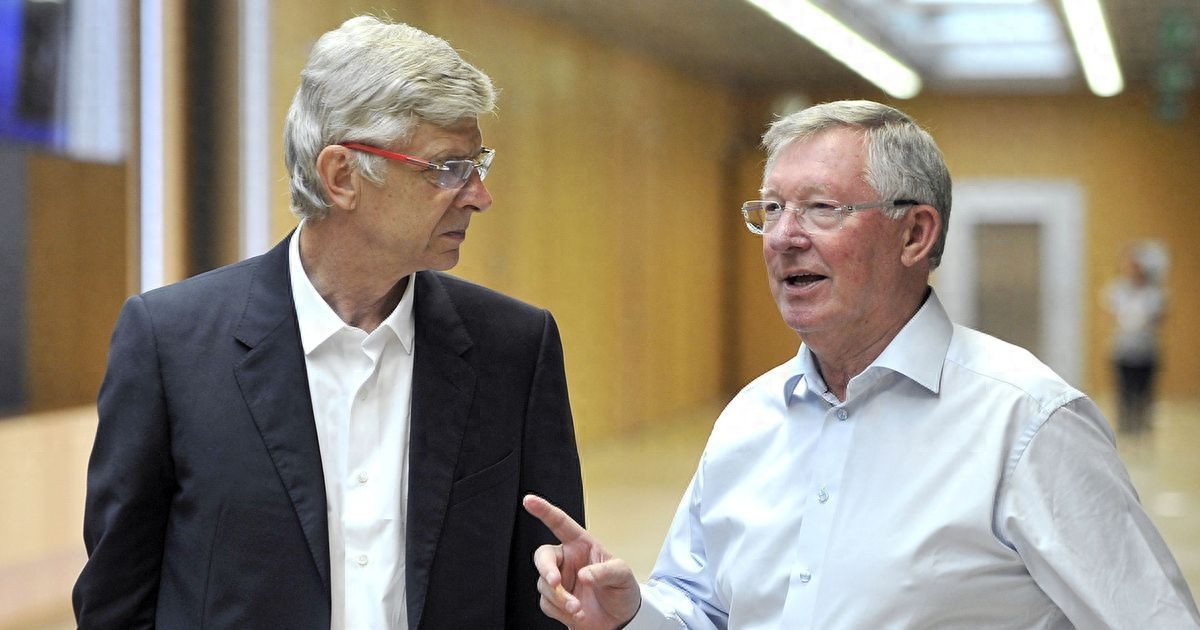

Against this backdrop, Premier League “managers” like Ferguson and Wenger, who oversaw every aspect, are becoming rare, replaced by more head coaches focusing solely on training and matches. Although this shift clearly contradicts football’s competitive traditions, the wave of capital investment ensures the traditional “manager” role will continue to decline.

Premier League managers halved in three years

In 2022, British Athletic published a detailed article discussing the debate between Premier League “Managers” and “Head Coaches.” At that time, 11 out of the 20 Premier League clubs still had head coaches with the “manager” title. Today, that number has dropped to six: Guardiola (Manchester City), Arteta (Arsenal), Emery (Aston Villa), Glasner (Crystal Palace), Moyes (Everton), and Farke (Leeds United). Even these six clubs have sporting directors leading separate football management teams supporting the first team. These directors are Hugo Viana (Man City), Berta (Arsenal), Vidagany (Aston Villa), Hobbs (Crystal Palace), Cox (Everton), and Underwood (Leeds).

Among the traditional Premier League big six, Liverpool and Manchester United are the latest to abolish the “manager” system. After Klopp’s departure last year, Klopp’s successor, Jürgen Klopp’s replacement, Slutsky, took the role of head coach only, while sporting director Richard Hughes leads a five-person management team. Slutsky accepted this division of power, as it aligns with common practice in continental Europe, including the Netherlands. The American Friedkin Group, which acquired Everton, eliminated the traditional football director role, establishing a “sports leadership team” headed by a sporting director to share responsibilities. This team reports to club CEO Kinil. Cox (sporting director), Smith (recruitment director), Howorth (strategy and analysis director), and Hammond (player trading director) each have defined roles. Cox oversees first-team operations, medical, logistics, and youth development, holding the greatest authority. Leeds United’s football management and recruitment team is even larger, consisting of seven members.

In the past, people expected head coaches to master player transfer negotiations. Ferguson dedicated a chapter in his autobiography to this topic. Besides that, he was responsible for training, matches, scouting youth players, and overseeing scouts. Sporting directors and their teams have taken on many of these duties and pressures, enabling a new generation of coaches in English football to specialize in training and match management. As a result, many new fans today might be surprised to hear the term “manager.”

However, whether titled manager or head coach, the role’s responsibilities and outcomes differ significantly. The “manager” title conveys a stronger message to the dressing room, club departments, and the outside world: it signifies control and autonomy over the first team. Former Tottenham coach Pochettino is an authority on the distinction between these titles. When he started in 2014, his title was head coach; two years later, it changed to manager: “Both the club and I agreed this was better for me, the club, and everyone involved.” Yet three years later, Pochettino admitted he had no say in transfers, which were decided by chairman Levy, meaning he was effectively still a head coach.

Title is symbolic, power is real

Mike Rigg, who has served as sporting director at Burnley, Fulham, and Manchester City, believes debating title semantics is pointless; people should focus on actual roles and responsibilities. Given the unprecedented scale, complex management structures, and diversified duties in modern football clubs, it is nearly impossible for any coach to fully control all aspects of a Premier League team. Still, some coaches try to oversee everything. Rigg contrasts this: “Some coaches want to focus solely on the first team to perform at their best, avoiding involvement in transfers, youth development, and other matters. Others want to control everything, turning it into a power struggle about the best way to develop the team.”

The cases of Maresca and Amorim demonstrate that Premier League elite clubs are increasingly limiting head coaches’ authority. Club owners, CEOs, and sporting directors expect head coaches to spend most of their time on the training ground, rather than delegating daily training to assistants while personally handling player transfers, contract renewals, and youth scouting. A senior Premier League executive said the manager title traditionally implied greater power for the holder, but former Tottenham coach Puel noted this model no longer exists.

In September 2020, Arsenal officially announced and explained why Arteta’s title changed from head coach to “first-team manager.” Then-CEO Vinai Venkatesham stated this was a reward for Arteta guiding the team through “perhaps the most challenging nine months in the club’s history”: “From day one, he did far more than the head coach title suggests. Beyond excellent first-team coaching, he contributed in many other ways. This title change recognizes his outstanding capabilities.”

Similarly, Emery at Aston Villa gained greater authority in a comparable manner. Appointed head coach in 2022, he was promoted to manager in 2024. Although Aston Villa’s football management and recruitment team numbers six, Emery’s influence over the first team is decisive. This situation also occurs at Manchester City under Guardiola. However, this successful manager model does not apply universally. Even with the head coach title, the level of control varies greatly among clubs depending on the preferences or strategic evaluations of owners and CEOs.

Unfortunately, positive examples of this “manager” system are very rare. Even Premier League fans have accepted and grown accustomed to the presence and dominance of sporting directors. This trend inevitably produces extremes like Chelsea’s setup with five directors alongside one head coach, or conflicts like those at Manchester United where disputes between directors and head coaches lead to coach dismissals. The commercialization of modern football naturally drives a business-first development direction, and under the principle of prioritizing interests, this is unlikely to be reversed.

Wonderfulshortvideo

The footwork, the finish 🤌

The Wirtz x Sané link-up 🔗

Class personified.

yamal getting better raphinha goals today raphinha vs osasuna yamal barcelona highlights yamal pass today

Griezmann with the cool finish 🥶

“afcon funny moments”

🤤🤤

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App