Federer: Is it true that slow courts were designed for ticket sales to benefit Alcaraz and Sinner?

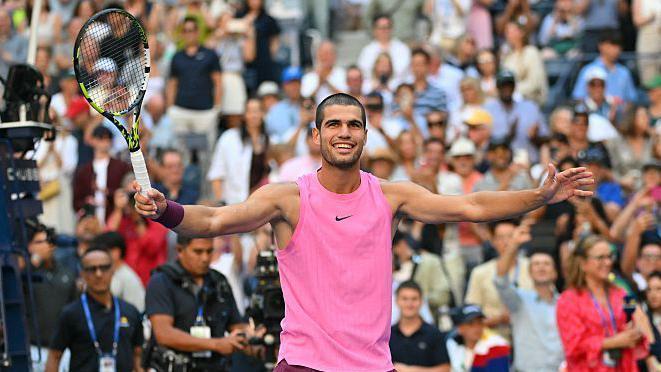

When discussing tennis expertise, no one is more qualified than the legend himself. Federer clearly understands the nuances of courts around the globe. After more than two decades as a pro and continuing involvement via his brand On and the Laver Cup, he recently expressed some unexpected thoughts, including his belief that today’s courts appear to advantage Sinner. His remarks sparked much speculation, and Sinner himself responded.

During the Laver Cup weekend in San Francisco, Federer shared his perspective on Andy Roddick’s podcast. He suggested that the standardized balls and court speeds nowadays make matches too predictable, benefiting star players like Alcaraz and Sinner.

Federer stated, “Obviously, I understand why they do this. It acts like a safety net for weaker players—if you want to beat Sinner, he has to hit exceptional shots. On faster courts, he might only need a few well-timed strokes. That’s the logic behind these decisions.” His words directly highlighted Sinner’s strengths.

At a press conference before the China Open in Beijing, world No. 2 Sinner was asked about this. He said, “Indeed, hard courts can sometimes feel very similar. Occasionally, there are slight differences, maybe a point or two. One example I can think of is Indian Wells, where the ball bounces quite high and behaves somewhat differently on the court.”

“Overall, the match patterns on court have been roughly the same for a long time. I don’t know if that will change in the future. I’m just a player trying to adapt in the best way possible. I think I’m doing well in that regard, but we’ll see what each upcoming tournament brings,” Sinner responded calmly and composedly.

Meanwhile, some netizens conducted an in-depth analysis of the courts based on Federer’s comments. One pointed out that the Laver Cup court, which Federer might have influenced, is unusually slow compared to many men’s tour events. To verify if courts are truly becoming uniform, this user compared two extremes in 2025: Monte Carlo (slow clay) and Cincinnati (clearly fast hard court). The data spoke volumes: Monte Carlo’s serve winner rate was only 5.3%, while Cincinnati’s was more than double at 12.3%.

Besides serve winner rates, rally length and the Court Pace Index (CPI) also revealed huge differences. Monte Carlo averaged 4.75 shots per rally, whereas Cincinnati had only 3.58. CPI showed a clear speed gap: 29 for Monte Carlo versus 43 for Cincinnati. This clearly indicates courts still significantly impact match dynamics, challenging the idea that “playing conditions are converging.”

There are also notable differences between grass and clay courts. For example, Wimbledon’s serve winner rate has stayed around 12% over the past decade, while the French Open is about 6%. Court surfaces matter greatly because they affect spin differently, and spin has become extremely important in recent years. Players are smart and constantly adjust their tactics, slice usage, and return strategies to suit the surface.

This is especially evident in the return strategies of Musetti and Fritz. Musetti’s forehand topspin and slice ratios vary by tournament—his 52-week average is 68% topspin and 32% slice, but on grass at Stuttgart and Queen’s, they are nearly even at 51% topspin and 49% slice.

In contrast, Fritz prefers a mostly topspin style, maintaining a 90% topspin to 10% slice ratio throughout the year. Even on grass events like Queen’s and Eastbourne, his ratio remains close to 71% topspin and 29% slice. This clearly shows players adapt their game depending on the surface.

The gap between Wimbledon’s 12% serve winner rate and the French Open’s 6% again highlights how court speed and spin shape playing styles. Players must adjust their slice frequency and return tactics to match the rhythm of different courts.

Why do Sinner and Alcaraz excel across all surfaces? Simply because they have almost no weaknesses. Their strongest weapons—serve, forehand, backhand, and return—are perfectly combined, allowing them to dominate matches from the start without needing other tactics to defeat opponents.

After the “serve boom” of the 1990s, court speeds slowed dramatically, hitting their lowest between 2007 and 2014. Since then, speeds have gradually increased, and now nearly 70% of men’s points finish within four shots. With today’s powerful players, even slow courts don’t necessarily extend rallies much, nor do fast courts always shorten them since hard courts are already quick. Interestingly, slow courts can sometimes encourage more variation, yet in 2025’s Grand Slams, Alcaraz and Sinner nearly dominated all events.

As for tournament organizers wanting top players to reach finals, this is nothing new. It is the essence of sports to identify the best player in the end. In most sports, reducing randomness and emphasizing skill has always been part of the rules. It’s hard to understand why this would cause controversy.

Both Federer and Sinner make valid points: current courts are indeed too similar. Tennis needs to return to true extremes—some genuinely fast courts and some truly slow courts—to restore diversity. Today, the only top-level event considered “medium-slow” is Indian Wells, while others (Australian Open, Miami, Cincinnati, US Open, Paris Masters, ATP Finals) cluster in the “medium-fast” range.(Source: Tennis Home, Author: Spark)

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App