Saying that female players are too "fragile" to play five sets is blatant gender discrimination.

The sport of tennis frequently grapples with controversies surrounding "gender discrimination." At this year's French Open, director Amélie Mauresmo was criticized for scheduling men's matches during prime time every night, leading to claims of "betraying women." In contrast, at Wimbledon, the situation was reversed—every one of the five finals was officiated by female umpires, which sparked some discontent among referees questioning whether diversity was prioritized over competence.

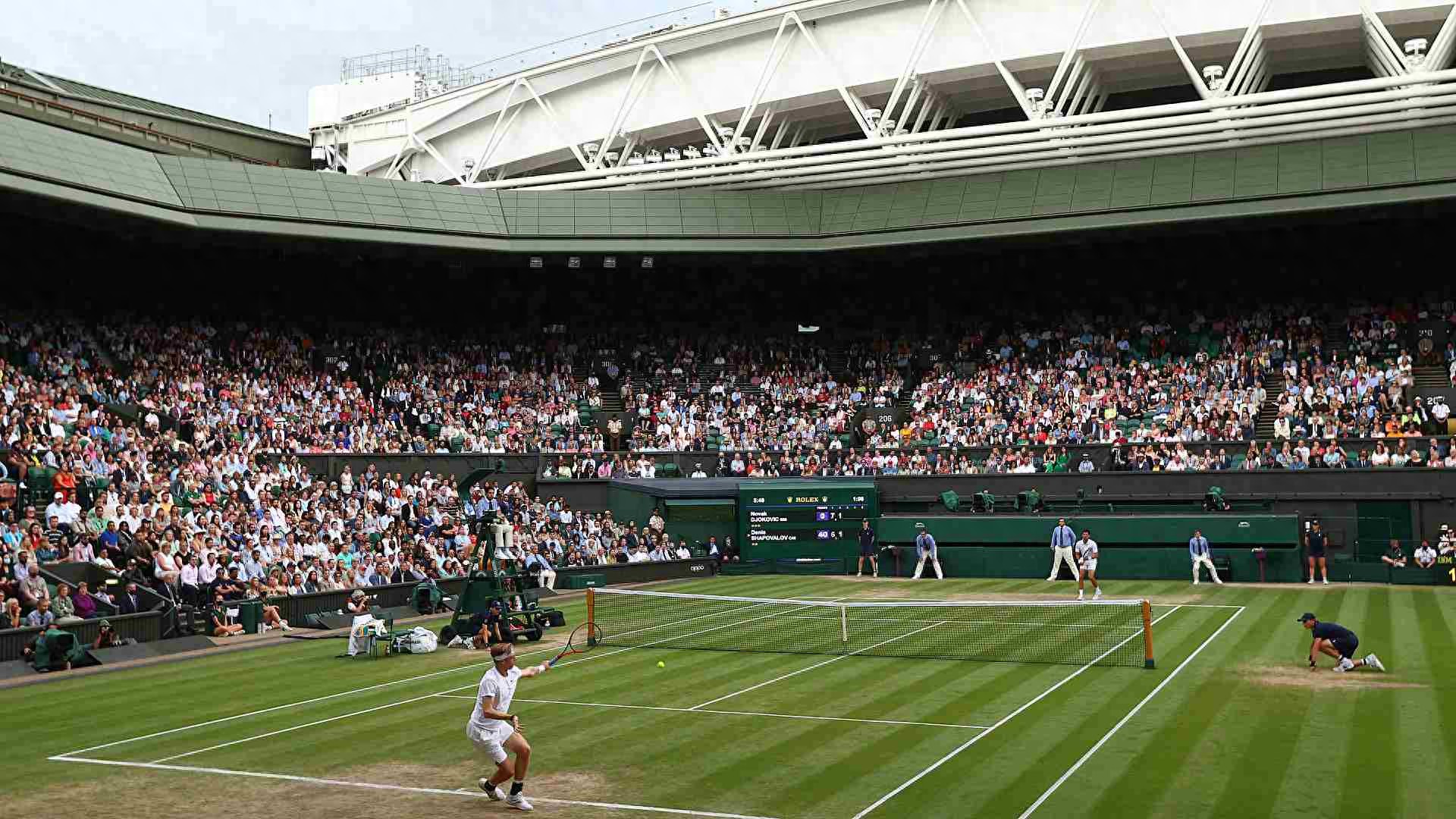

However, while the match where Anisimova was decisively defeated by Swiatek sparked discussions, the tennis world continues to overlook a deeply rooted inequality: women are still seen as too fragile to endure the full physical demands of a complete match format, thus relegating them to "condensed" competitions. In the Wimbledon women's singles final, American player Anisimova was "double-bagelled" by Swiatek, with the match lasting only 57 minutes, marking the most lopsided score in 114 years. Meanwhile, Alcaraz and Sinner were just entering the second set of their classic encounter, which lasted 3 hours and 4 minutes. This further demonstrates that the best of five sets format is fundamentally different in entertainment and tension compared to the best of three sets format.

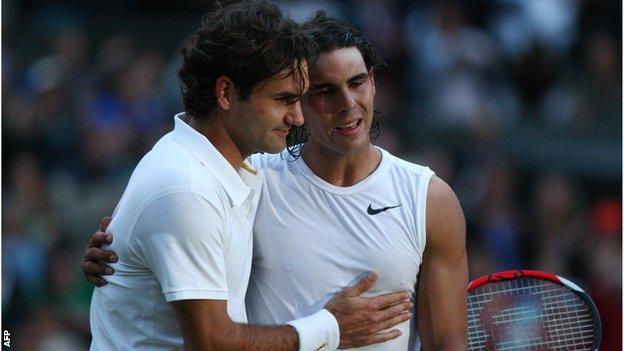

This disparity becomes even more pronounced during the critical stages of Grand Slam tournaments. In 2019, Djokovic and Federer battled for nearly five hours on Centre Court before a winner emerged, while that same year, Serena Williams was swept away by Halep in just 56 minutes. For instance, at the 2012 Australian Open, Azarenka defeated Sharapova 6-3, 6-0 in 1 hour and 22 minutes; in contrast, Djokovic and Nadal's subsequent match lasted 5 hours and 53 minutes, making it one of the toughest Grand Slam finals in history. One match was over in an instant, while the other became an eternal classic. These differences are not coincidental but are based on an underlying gender bias: the belief that women's bodies cannot withstand the intensity of five-set matches.

Debates over scheduling, whether female players receive adequate exposure on central courts, and why the women's singles final is held on Saturday instead of Sunday are merely "smoke screens" that distract from the core issue—why is the match load so unequal between genders? Do we really believe that 2025 women's singles champion Swiatek cannot handle a five-set match? This absurd notion was already dismissed in the late 19th century: in the 1892 U.S. National Championships (the precursor to the U.S. Open), Mabel Cahill defeated Bessie Moore in the women's singles final after a grueling five-set battle, with scores of 5-7, 6-3, 6-4, 4-6, 6-2.

Swiatek's "dominant victory" over Anisimova in a match that was hardly worth watching seems to have finally made some people aware of the issue. "This is exactly when you wish the women's singles final was a best of five," Laura Robson remarked while commentating on the one-sided match. "If she (Anisimova) had more time to find her rhythm, the outcome could have been completely different." Her perspective is realistic and valid: in the 2004 men's singles final at the French Open, Gaudio was crushed in the first two sets by Coria with scores of 6-0, 6-3, but due to the best of five format, Gaudio miraculously turned the match around to win.

When Wimbledon announced equal pay for men and women in 2007, the decision was hailed as a historic milestone. Billie Jean King—an important figure in the fight for gender equality in tennis—called it an "obvious decision" and had long advocated for "equal pay." However, the reality is that there is no true "equal work" in Grand Slam events; despite equal prize money, the significant difference in match length effectively means that male players are "underpaid." At the 2016 Australian Open, men's singles champion Djokovic spent far more time on the court over seven rounds than women's singles champion Kerber, earning £56,000 less per hour than her.

Even Nadal, known for his mild demeanor, has expressed reservations about the blunt implementation of equal prize money, arguing that compensation should correlate with the revenue and spectator interest generated by the players. Perhaps the most elegant solution would be to introduce the best of five format for women's matches at least during the later stages of Grand Slam tournaments (from the quarter-finals onward). While scheduling both genders to play five sets in the same event does pose complex logistical challenges, implementing this arrangement from the quarter-finals onward should be feasible, especially given that prize money significantly increases with each round progressed.

As for endurance differences? Please dispel that misconception. Research shows that the longer the physical challenge lasts, the smaller the performance gap between men and women becomes. In certain ultra-endurance events, the difference can be as little as 4%. The perception of women as "naturally fragile" in tennis is incorrect. In 2008, Venus Williams won her fifth Wimbledon title by defeating her sister in straight sets, and just two hours later, the sisters teamed up to win the doubles title. Can you imagine Federer and Nadal immediately returning to the court after their classic four-hour and 48-minute men's singles final that ended at dusk?

Therefore, we should stop "pretending" that best of three matches can be equated to best of five matches, and use Swiatek's "double-bagel" victory as an opportunity to advocate for "equal work" alongside "equal pay."(Source: Tennis Home, Author: Spark)

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App